- Free schools for IDP children in Arakan State struggle to stay open amid funding shortfall

- Female-headed IDP households in Ponnagyun Twsp struggle as commodity prices surge

- Min Aung Hlaing likely to take State Counsellor role in post-election government formation: Analysts

- Hindus express hope for educational reform under AA administration

- Arakanese zat pwe performers struggle to survive as conflict halts traditional shows

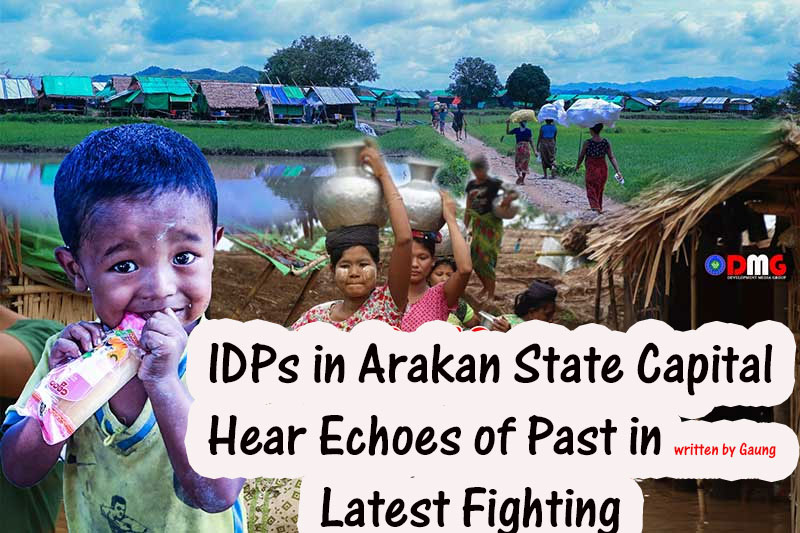

IDPs in Arakan State Capital Hear Echoes of Past in Latest Fighting

Living conditions in IDP camps are especially stressful for women and adolescent girls. Privacy is essentially nonexistent, whether bathing, changing clothes or using the toilet.

31 Aug 2022

Written By Gaung

“I’m not happy with my fate; to have been born and raised in an unstable region,” said 58-year-old Daw Ma Sein Nu, who had been recently displaced from her village, Seint Nyin Wa in Chin State’s Paletwa Township, when DMG spoke to her in July.

She said she had never dreamed of living the life of an internally displaced person (IDP), but now she and her family are taking shelter at a displacement camp in Sittwe, the capital of Arakan State. The camp is located in Mingan ward, within the compound of a Buddhist monastery there.

Clashes between the Myanmar military and the Arakan Army (AA) first erupted in Arakan State and parts of adjacent Chin State in 2015, and intensified in late 2018.

By the time the fighting had reached its peak in April 2019, many villages were deserted by their residents. Daw Ma Sein Nu’s family fled their home when clashes nearby escalated, with the Myanmar military using jet fighters and Navy vessels, as well as artillery strikes, to attack the Arakan Army. They arrived at the IDP camp in Sittwe via Kyauktaw.

“We had to climb around seven to eight mountains before crossing Pe Creek in the evening. We couldn’t use torchlights. Their aircraft fired shots when they saw lights. We were starving and we had only water to drink,” Daw Ma Sein Nu recounted.

Some fleeing families had infants and toddlers whose needs were neglected as their parents fled for their lives through the forests. Some women were heavily pregnant, and some had only recently given birth, said Daw Ma Sein Nu.

Many IDPs left behind their life’s savings as they hurriedly sought safety away from the fighting. More than two years after their displacement, many still live in makeshift tents made of tarpaulin sheets and bamboo, frequently going hungry and constantly worrying about their future.

The displaced women and children all ask the same question: “When will we be able to go home?”

Women and children make up about 70 percent of the displaced populations in the IDP camps.

“There is little privacy for adolescent girls. I have an adolescent boy and girls. You needn’t wonder whether this room is suitable for them or not,” said IDP Daw Ma Thaung, pointing to a tiny room.

Daw Ma Thaung, 56, is also from Seint Nyin Wa in Paletwa Township. Her husband died 10 years ago, leaving Daw Ma Thaung, their son and two daughters behind. But Daw Ma Thaung says she managed to lead a decent life in her native village until she was forced by clashes to take shelter at the Buddhist monastery in Sittwe, some 100 miles from her village.

The tiny room that is now home to the four-member family is bursting with an altar, bed sheets, kitchen utensils and clothes. The room is used as a dining room, bedroom, anteroom and reading room, she said.

“We have to live in this tiny room. The worst thing is that my younger daughter can’t read [properly in such a small room],” she said.

The junta’s Ministry of Social Welfare, Relief and Resettlement, the World Food Programme, International Committee of the Red Cross and other humanitarian and social organisations provide food supplies for them, but those provisions are not enough, Daw Ma Thaung said.

Women, Children Face Particular Vulnerabilities

Living conditions in IDP camps are especially stressful for women and adolescent girls. Privacy is essentially nonexistent, whether bathing, changing clothes or using the toilet.

Women at IDP camps suffer from emotional insecurities and material deprivations, and some are battling depression as a result, said Daw Ma Thaung.

Arakanese women’s organisations say that local women in northern Arakan State have been subjected to psychological and physical violence by Myanmar military forces.

“There was a lot of psychological and physical violence against women during the armed conflict,” said Daw Nyo Aye, chairwoman of the Rakhine Women’s Network. “There is only one woman from Ugar village in Rathedaung Township who has bravely spoken out about violence and rape. We have received information [about other cases] but the stakeholders begged us not to go public [with their stories], so it was not possible to speak at all.”

She went on to say that there are cases of child rape and abuse of women in the displacement camps, and effective protection against these crimes as well as post-trauma rehabilitation programmes by relevant government authorities and international organisations are weak.

“No organisation, including the government, has done anything effective to heal the emotional and physical pain of women in IDP camps. The main stakeholder in [addressing] this issue is the government. If the government cannot address this problem, other organisations have not been effective in this regard either,” she added.

Chapter 3, Article 9(m) of the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA), officially signed between the Myanmar military and 10 ethnic armed organisations, states that women should not be subjected to rape, sexual violence, forced concubinage, sexual abuse, or sexual slavery. And yet women are held hostage in various ways in Myanmar’s conflict zones, where forcible abductions and gang-rape are also far too common. In addition, due to the presence of armed forces in connection with the conflict, teenage girls are worried that they will be subjected to violence.

In Article 9(n) of the NCA, it is agreed: “Avoid killing or maiming, forced conscription, rape or other forms of sexual assault or violence, or abduction of children.”

Legacies of Conflict

In the past, men, women and children were free to move and live without fear of any armed forces. Since the fighting started in these villages, however, locals worry about the danger of landmines and explosive remnants of war, as well as fearing the nearby movements of the warring armed groups.

Chapter 3, Article 9 of the NCA is entirely devoted to civilian protection, while Article 10(b) states that internally displaced people (IDPs) should be allowed to resettle in their original areas according to their wishes, or establish a new village at a suitable location in a safe and dignified manner. But government authorities have not followed through on the implementation of these provisions in accordance with the human dignity of IDPs.

Back in their native villages, IDPs say that even if they were not well-off, they could make a decent living growing seasonal crops and raising livestock. But at the displacement camps, they have no jobs, crops or cattle.

“Now there are no job opportunities here. Also, since we have become old, we are no longer hired as workers,” Daw Ma Thaung said, adding that the gold jewellery she had brought with her when she fled had to be sold piece by piece whenever a family financial crisis arose in the displacement camp.

Before the fighting, locals in the village of Seint Nyin Wa, which had about 130 households, grew crops such as sesame and groundnuts, and made a living by farming on both small plots of land and plantations.

Daw Ma Thaung said all of the houses in Seint Nyin Wa village were burnt to ashes due to the armed conflict, describing what remains as a ghostly ruin.

As a result of the fighting, more than 20,000 local people from more than 30 villages in Paletwa Township were forced to flee the war, the Relief and Rehabilitation Committee for Chin IDPs (RRCCI) said in May 2020, more than five months before the two sides reached an informal ceasefire.

The military junta has held peace talks with 10 ethnic armed groups in recent months, but those discussions did not include the Arakan Army, the Chin National Front or any of the anti-regime groups that have sprung up since the coup and now have a presence in Chin State. In northern Arakan State and Chin State, tensions have been rising for months, and clashes have been reported in recent weeks with alarming regularity.

What’s more, women have continued to face underrepresentation in the junta-led peace process, as was the case under previous civilian and military governments.

“We women suffer more because of the war. We do not understand any politics. So we want the military and ethnic armed groups to hold peace talks,” said Daw Ma Sein Nu.

.jpg)