- Fuel prices triple in Sittwe, forcing some stations to close

- Iran crisis sparks fuel price hikes in AA-held areas

- Arakan residents gripped by fear as junta airstrikes intensify

- Junta personnel, police and families evacuate Sittwe for mainland Myanmar

- Muslim armed groups killed 162 civilians in two years in northern Arakan: HDCO report

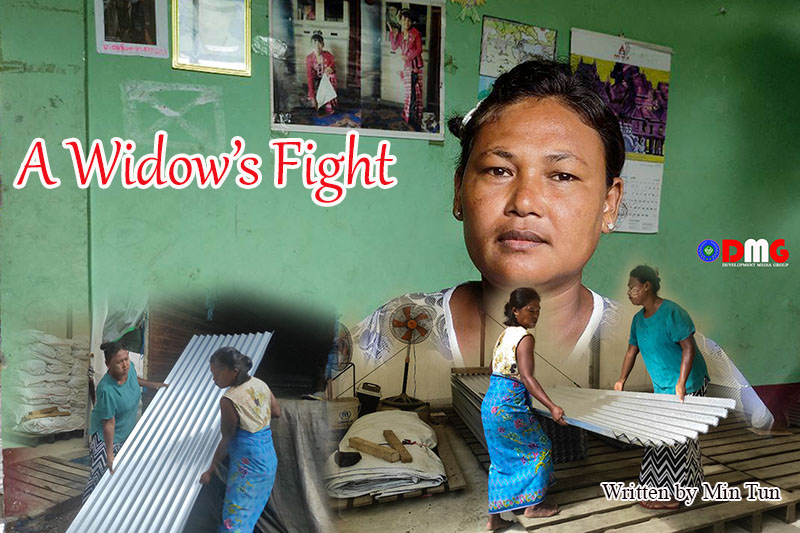

A Widow’s Fight

Daw Sandar’s eldest daughter currently attends a government technical high school in Sittwe and her younger daughter is a Grade 8 student.

30 Nov 2022

Written by Min Tun

Among the porters who were unloading the truck were some women. Daw Sandar, 37, is the forewoman of a 20-odd workforce including seven female workers who eke out a living unloading cargo trucks for long-distance cargo trucks at the transport terminal in Sittwe’s Shwepyithar Ward, in the capital of Arakan State.

It is not a regular job, as cargo trucks from Yangon only arrive a maximum of four days a week these days, sometimes less. Mainly, they have to unload foodstuffs, household goods and pharmaceuticals.

“Our wage depends on the number of cargo trucks we unload. It is best if we can unload three vehicles or more a day,” said Daw Sandar.

They are paid K50,000 to unload a 12-wheeled truck, and K30,000 for a six-wheeled truck, and the money is equally shared among them. In the rainy season, 12-wheeled trucks usually do not come, and they mainly have to rely on six-wheeled trucks.

“The amount of money also depends on the number of workers. Normally, 10 people work for a truck, and each earns K3,000. However, if there are only five people, each earns K5,000,” she said.

Despite the adverse circumstances and hard-earned sweat, Daw Sandar is struggling to make ends meet due to soaring food costs.

“Food prices have increased a lot. As workers rely on daily wages, none of us can keep pace with rising commodity prices. No need to say what happens to us on days when we have no job,” she explained.

Rising costs of living are taking a heavy toll on low-income families in post-coup Myanmar.

Daw Sandar is a widow with two children. Her husband died when she was 27, after 10 years of marriage. At the time, her oldest daughter was just 9 years old, and the younger daughter was only 2 years old.

She has since shouldered the burden of parenthood for her two daughters, doing various casual jobs including carrying gravel and sand, and as a bricklayer, to make ends meet.

“I worked hard, telling myself it is shameful if I can’t afford to feed my children,” said Daw Sandar.

Daw Sandar’s eldest daughter currently attends a government technical high school in Sittwe and her younger daughter is a Grade 8 student.

Her eldest daughter passed her third year, majoring in Electrical Power (EP) at a government technical high school in Sittwe with a two stars grade. Therefore, she will have to continue teaching this subject at the Government Technical Institute (GTI) in Thandwe for another three years. Her eldest daughter is going to Thandwe in December 2022. Daw Sandar, who continues to earn a living as an odd-jobs worker, is worried.

No matter what challenges arise, she is determined to support her daughters’ education, said Daw Sandar.

“I want my children to be educated people. I don’t want them to be inferior to others. If they are educated, they can work anywhere with their education. I want my children to be educated because I don’t want them to feel like me,” she told DMG.

Daw Sandar’s family currently live in a rented room in Sittwe’s Shwepyitha Ward, where the monthly rent is K100,000.

“To this day, no matter how difficult I am, I only shed tears. To this day, I have not remarried because I love my children,” she said.

Daw Sandar aims for her two daughters to one day stand on their own feet, with integrity and dignity.

“I want to see my two daughters become educated in my life. Even if their marriages fall apart, they will not be inferior to their husbands. They can make a living with their own skills and work; people are not treated with contempt. If you are poor but educated, you can still get people’s respect,” she said.

Daw Sandar said that when faced with the lack of jobs and food shortages in Arakan State, she thought of going abroad to find a way out and work, but she couldn’t leave her two daughters and was not reliable, so she decided not to go.

“I am most afraid that my children will do something when I go abroad for work,” Daw Sandar said, reflecting a common conundrum faced by families with migrant workers in their midst.

.jpg)