- Only two Arakan political prisoners freed in junta’s Peasants’ Day amnesty

- Fuel prices triple in Sittwe, forcing some stations to close

- Iran crisis sparks fuel price hikes in AA-held areas

- Arakan residents gripped by fear as junta airstrikes intensify

- Junta personnel, police and families evacuate Sittwe for mainland Myanmar

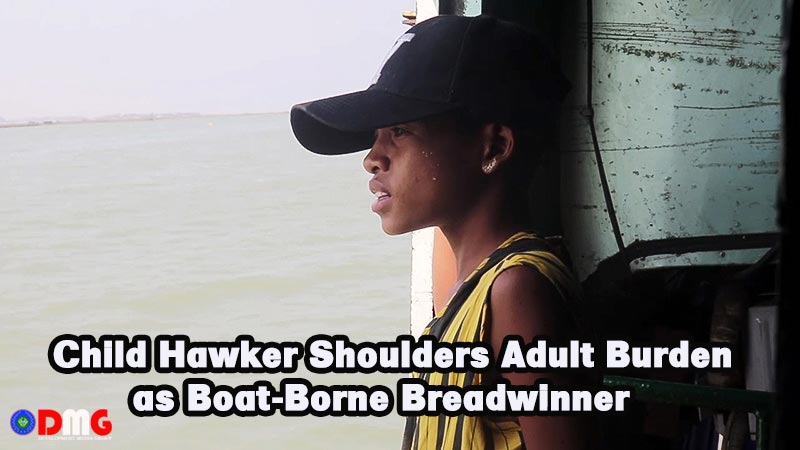

Child Hawker Shoulders Adult Burden as Boat-Borne Breadwinner

The voice of a quail-egg hawker is clearly heard on a vessel from the Shwe Pyi Tan express boat line amid the din of passengers’ chatter and the engine of the boat.

03 Jun 2021

3 June | DMG

The voice of a quail-egg hawker is clearly heard on a vessel from the Shwe Pyi Tan express boat line amid the din of passengers’ chatter and the engine of the boat.

Thirteen-year-old Maung Maung Naing earns his living by selling quail eggs on the express ferry, which plies a route between Pauktaw and Sittwe towns in Arakan State.

He lives in a small hut at the edge of a ward in Pauktaw town. His parents have been separated since he was 11, and he and his mother are struggling to make ends meet.

The mother and son must work early in the morning, when most people are still asleep. They pack the boiled eggs and boiled peanuts in plastic bags each morning. Then, he sets off for the jetty, about a 30-minute walk from his home.

He sells boiled peanuts and eggs to passengers at the jetty, and then boards the boat bound for Sittwe. His hawking voice — “Boiled eggs and peanuts!” — cuts clearly through the other noises typical of maritime travel of this nature.

His daily life is not as idyllic as some other children’s. Most kids don’t have to worry about product and prices and daily sales targets.

He buys quail eggs from Sittwe for K3,000 per 100 eggs, and peanuts from Pauktaw for K6,500 per basket. Some days, he cannot sell the boiled peanuts because he does not have enough capital to invest.

“I boil about 200 to 300 eggs a day, in the early morning. I pack nine eggs in each package,” Maung Maung Naing said.

For vendors like Maung Maung Naing, the boat offers two chances to entice passengers each day.

“The boat departs at about 8 a.m. from Pauktaw and reaches Sittwe at about 9 a.m. In the afternoon, it departs at about 1:30 p.m. from Sittwe and reaches Pauktaw at about 2:30 p.m.,” he said.

If there are many hawkers on the boat bound for Sittwe, he might instead be found selling on the ferry headed for Minbya or Myebon. If sales are not good, he will forgo rice and curry for lunch and instead settle for a bowl of monti (Arakanese traditional noodles), which is cheaper than rice and curry.

He arrives home at 3 p.m., giving all the money and leftover eggs and peanuts to his mother. The next day, he’ll do it all over again.

Before he was hawking boiled eggs and peanuts, he helped his mother Daw Hla Sein Nu selling bamboo on the boats of the Shwe Pyi Tan boat line and others. When she got older and sick, she felt she had to send her youngest son into the workplace, though she did so with sadness.

Daw Hla Sein Nu has eight children, but does not get any financial contributions from the others, nor from her husband. So the burden has fallen to 13-year-old Maung Maung Naing to earn their living.

His future, and whether he should continue going to school or not, is unclear. His mother’s dream for him is that he becomes a teacher, but it is difficult to make that dream come true under their current circumstances.

Maung Maung Naing is a smart student and has been awarded prizes in school sporting competitions. But the discouraging reality is that time spent continuing his education is time not spent making money.

“He is a bright student in the classroom. He is good at playing football as well. He was awarded first prize at a school football match,” Daw Hla Sein Nu said.

“In previous years, his teachers told me they would help him pursue his education because he is a good student. I sometimes did not need to pay his education expenditures. Sometimes, I paid half of the expenditure,” she added.

Their hut in Pauktaw is a nominal shelter unlikely to fare well against the strong winds and heavy rains that characterise the monsoon season.

But Maung Maung Naing is not disappointed with his life. He has made up his mind to try his best to be a son, seller and student — and even gets a chance to play football, his favourite hobby, with friends in the evenings after work.

“When I arrive home, I play football or cane ball. Then, I carry water home and have a bath. I go to bed early at night because I will have to get up early to prepare for selling eggs at the jetty and on the boats,” Maung Maung Naing says of his bread-winning routine.

.jpg)