- 46 CSOs urge revolutionary forces to resolve internal disputes peacefully

- ARSA resurges with abductions and ambush attacks in northern Maungdaw

- Junta airstrikes disrupt education for students in Arakan State

- Arakan State records highest toll as 63 women killed in junta attacks in February: advocacy group

- Two civilians killed, one missing in ARSA mine ambush in Maungdaw

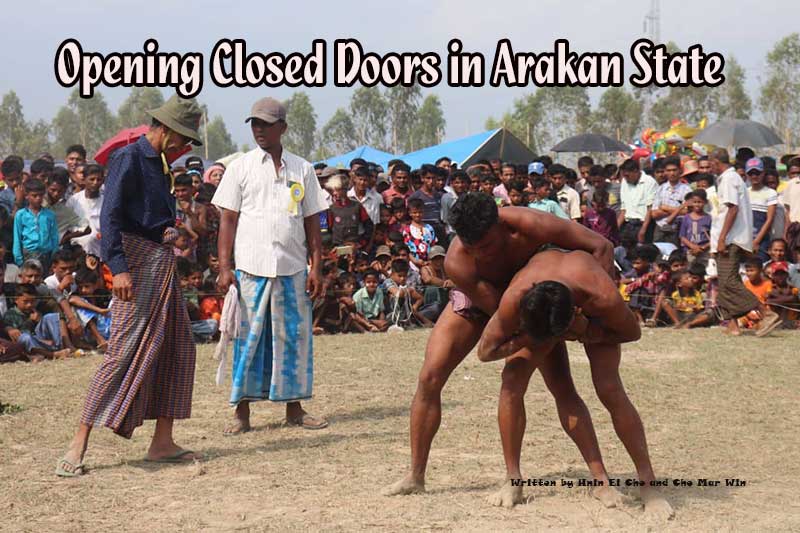

Opening Closed Doors in Arakan State

Last year, AA officials came and met with Muslim faith leaders, Buddhist monks and community elders, and called for peaceful coexistence between the two communities. It was followed by members of the two communities getting back in contact with each other after a lengthy gap in communications for many.

27 Jul 2022

Written by Hnin Ei Cho and Cho Mar Win

One fine afternoon in May, Arakanese and Muslim people gathered at a pagoda in the Kan Pe area of Minbya Township; a rare sight in conflict-wracked Arakan State.

When the annual pagoda festival was held at Paw Taw Mu Pagoda from May 2-4, an opportunity arose for the two communities to bury the hatchet. The pagoda festival traditionally features a wrestling competition, and this year the two communities decided to organise this competition for Muslims too, looking to harness the power of sport to unite, and foster tolerance and social inclusion.

There are 14 Arakanese villages and four Muslim villages in the Kan Pe area. Historically, the annual pagoda festival was jointly organised by the local Buddhist and Muslim communities. But after Arakan State was rocked by sectarian strife in 2012, tensions arose between the two communities and trust was shattered.

Arakanese villagers organised the pagoda festival in 2013 without the involvement of local Muslims. This was the case for the next several years as well.

But the two communities have lately made strides toward restoring ties and rebuilding trust and friendships, with Arakanese villagers visiting Muslim villages and vice versa. This year’s Paw Taw Mu Pagoda festival is further testament to the notion that relations between the two communities are improving: Local Muslim residents joined Arakanese Buddhists at the pagoda festival for the first time since 2012.

“We have had no festival since the strife, and we had nothing to enjoy all those years,” said Muslim villager Ko Kyaw Maung Che from Nona village.

In the past, Arakanese and Muslim people were business partners. Arakanese businessmen employed Muslim employees, and vice versa. But the business community, too, was riven by the 2012 communal violence.

“As we were not allowed to enter Arakanese villages, we could not sell rice. We had to sell rice at lower prices to buyers. Some even starved because we could not work in Arakanese villages,” said U Tin Shwe, from Tan Seik Muslim village.

The Arakan Army (AA) has claimed credit for playing a major role in repairing relations between the two communities.

Last year, AA officials came and met with Muslim faith leaders, Buddhist monks and community elders, and called for peaceful coexistence between the two communities. It was followed by members of the two communities getting back in contact with each other after a lengthy gap in communications for many.

“The AA has told the Arakanese people not to do any harm to Muslim people when they visit Arakanese villages. We can also enter towns,” said U Ba Thaung, head of Sapkya Muslim village.

“Muslim patients can also be admitted to a public hospital in Minbya. In the past, Muslim patients were only allowed to visit the clinic in [neighbouring Mrauk-U Township’s] Myaung Bway village,” he added, referring to severe restrictions on travel for Muslims, even just between townships, following the 2012 conflict. Across much of Arakan State, travel restrictions remain in place for the state’s Muslim population.

Nonetheless, a decade of closed doors separating Buddhist Arakanese and Muslims have been reopened in recent years.

“Relations between Arakanese and Muslims are currently said to be good because there is always a dialogue between Arakanese and Muslims. We tell the Arakanese young people that we should build better relations between the two communities, and they also accept it,” said U Tin Aung Than, an Arakanese man from Kyetmagyi village.

“Relations between the two communities are good, as both sides understand what the elders have discussed. We have to consult with Muslims and make the best of it,” he added.

“Muslims also donated as much as they could to the festival of Pawdawmu Phayarpaung Pagoda. I am glad that the Muslims have joined in the pagoda festival happily, regardless of race or religion,” said U San Tun Hla, chairman of the pagoda board of trustees in Nardin (Arakanese) village.

“We intend to work with Muslims. We will always invite Muslims to join us,” he said with a smile.

Many locals believe that peaceful coexistence between the two communities is necessary if Arakan State is to overcome the entrenched poverty that has characterised both communities for decades.

“Now, the relationship between the Arakanese and the Muslims is much better than before. And we will try to keep improving the relationship between the two communities,” said Ko Kyaw Maung Chay, who came to take part in the traditional Muslim wrestling contest at the Paw Taw Mu Pagoda festival in May.

“I hope the relationship between the Arakanese and Muslims will be even better in the future,” he added.