- Over 1,600 students sit for matriculation exams in three regime-held townships in Arakan State

- DMG Editorial: The Military Junta Is Openly Killing Its Own Soldiers in a Revolting Act

- Merchants struggle under NUG fuel transport restrictions in Arakan State

- Nearly 500 flee homes after junta airstrike on POW detention site in Ann

- Fuel prices double in Arakan Army-held areas amid panic buying

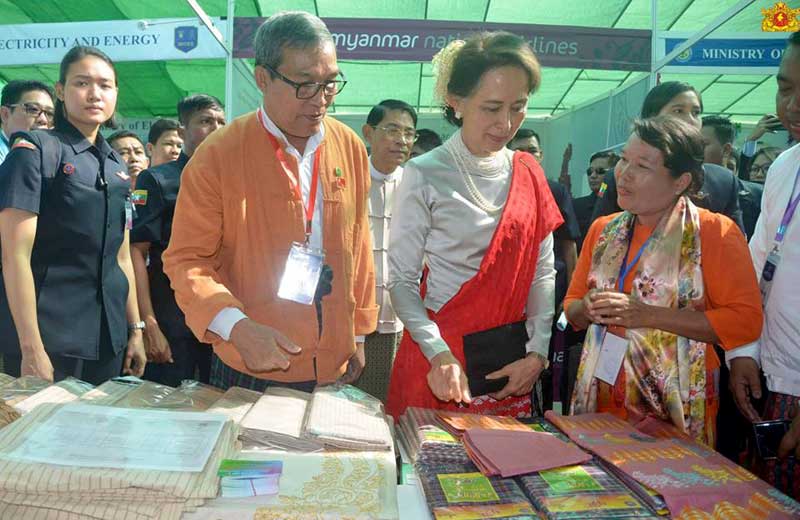

The NLD’s Broken Promises in Arakan

Myanmar is gearing up for a general election later this year that will pit the NLD against dozens of other political parties including many “ethnic” alternatives. Mindful of the looming polls, here we evaluate the extent to which the NLD government has delivered on these key commitments — to the rule of law, finding political solutions and federal principles — in the context of Arakan State.

27 May 2020

Aung Kyaw | DMG

27 May 2020

Long before holding governing powers, Myanmar’s de facto leader Aung San Suu Kyi had branded herself as a rule of law champion; she would use every opportunity to reiterate its importance. In fact, when she was first sworn in as a member of Parliament in 2012, the first committee she was asked to head was the “Committee for Rule of Law and Stability”.

At numerous peace process gatherings, she has been heard urging those engaged in armed struggle for autonomy to resolve political problems through political means and dialogue. And as she reminded the audience at the fourth anniversary of the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (or NCA, which is indeed an agreement but is neither nationwide nor a ceasefire proper), the National League for Democracy (NLD) has always been committed to federal principles, and to building a democratic, federal union.

Myanmar is gearing up for a general election later this year that will pit the NLD against dozens of other political parties including many “ethnic” alternatives. Mindful of the looming polls, here we evaluate the extent to which the NLD government has delivered on these key commitments — to the rule of law, finding political solutions and federal principles — in the context of Arakan State.

Woes of War and Rule of Law

On January 4, 2019, the Arakan Army (AA), a relatively new rebel group enjoying massive support among ethnic Arakanese (Rakhine), attacked four police posts in northern Arakan State by way of announcing that they intend to establish a lasting presence in the Arakanese’s ancestral homeland. This marked the informal beginning of a worsening and spreading armed conflict in Arakan and neighbouring southern Chin State. Unsurprisingly, this daring move from the AA struck a raw nerve with the powers that be in Nay Pyi Taw.

Later that month, a Myanmar military spokesperson said State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi herself had personally instructed the armed forces to crush the AA, which is what they have been trying to do ever since. It is not that the military, or Tatmadaw, needed permission or instructions from her government, as they exist and operate independently. However, her blessing gave the military carte blanche, which they have used liberally to carry out extrajudicial killings, torture and arbitrary arrests of civilians (in some cases rounding up entire villages).

As the AA has proven to be a much more tenacious force than initially thought, the Tatmadaw have been using greater firepower, including the use of heavy artillery and aerial bombings; tactics that inevitably result in a high civilian casualty count and destruction of property. The list of dead and wounded grows longer every week. For instance, 21 civilians were killed and 27 others were injured in a series of airstrikes in southern Chin State in mid-March of this year. Seven more civilians including two children and an infant were killed on April 8 and at least four more were killed during the third week of April.

Civilians are also being subjected to torture. The story of village carpenter Than Hlaing Win, who told his mother before dying about torture at the hands of Tatmadaw soldiers, is one of many such cases. According to Radio Free Asia (Burmese), there were at least 15 civilians whose families suspect that they died after being tortured by Tatmadaw soldiers in 2019. In late April of this year, a 27-year-old man from Mrauk-U Township was arrested at a Tatmadaw checkpoint and tortured to death, with his body dumped at the local hospital the next day. In the second week of May, a video of soldiers torturing five men in blindfold went viral, forcing the military to make a rare acknowledgement of wrongdoing.

Mass arrests of local villagers in the vicinity of fighting are also becoming routine. In an early incident of this nature, nearly 300 residents of Kyauktan village, Rathedaung Township, were detained on suspicion of having ties to the AA on April 30, 2019, and eight of them were shot dead while in custody. Although most of those rounded up were later released, six of them spent more than a year behind bars awaiting trial before being released earlier this month for lack of evidence. Two underage suspects remain in custody.

As news reports from numerous media sources indicate, this is not an isolated case but rather one of many. It is worth noting that the presidentially appointed Myanmar National Human Rights Commission did probe the Kyauktan village incident. Sadly, following their “investigation” the commission released a meaninglessly watered down statement, to the disappointment of many human rights activists.

By designating the AA as a terrorist group, positioning it for much harsher treatment than other ethnic armed organisations, the NLD government not only has legalised but also legitimised the actions of the military in Arakan State, which the outgoing Special Rapporteur on Myanmar Yanghee Lee has suggested could amount to war crimes. With an alarming civilian death toll, widespread torture and mass arrests becoming routine for the Tatmadaw — i.e., as the rule of law is upended — it has triggered little response from Aung San Suu Kyi. When she did speak up, she praised the “courage and dedication” of Tatmadaw soldiers!

Shrinking Political Space

In calling for political solutions to Myanmar’s problems, both army chief Min Aung Hlaing and Aung San Suu Kyi are alike. Ironically, they are also alike in shrinking the political space where ordinary citizens and politicians are supposed to find these solutions. Never mind the fact that it would be impossible to achieve any worthy political objectives — be they democratic, federal or both — under the extremely limited framework of the 2008 Constitution, which is neither democratic nor federal, and instead confers and enshrines undemocratic powers on the military. Athan, a local civil society organisation monitoring freedom of expression in Myanmar, recently reported that citizens’ right to free speech, which is fundamental to any functioning democracy, has declined under the NLD government, with the ruling party and the Tatmadaw being among the top violators.

Of course, an ongoing war creates all sorts of pretexts for the government and military to carry out further political suppression in Arakan. In addition to the mass detentions of local villagers discussed earlier, a number of Arakanese politicians and critics have been arrested and sent to prison on lengthy sentences. Dr. Aye Maung and the writer Wai Hun Aung were each given 20-year sentences after a court found them guilty of high treason and incitement in March 2019. In any democracy worth its name, the “crimes” for which the duo have been punished would have been shrugged off as an example of citizens exercising their freedom of speech. All they did was speak their minds in public.

In more recent developments, three individuals from Taungup Township were arrested and face dubious charges under Section 50(a) of Myanmar’s Counter-Terrorism Law. One serves as chairperson of the township municipal committee, another is his predecessor and the third is vice chair of the local Arakan National Party chapter.

The last straw that may have broken the camel’s back in Arakan State was the announcement on May 20, 2020, by the Union Election Commission that Dr. Aye Maung had been disqualified as an Arakan State MP and was banned from ever again running for a parliamentary seat. It drew criticism from politicians and commentators; as ANP spokesperson Aye Nu Sein put it, “It is an act of political oppression. Well, to put it more bluntly, it has turned into political castration.”

All of these developments over the past four years have created a climate of fear, which of course stifles political activism and is hardly conducive to finding the political solutions that Aung San Suu Kyi has called for.

Federal Mirage

Dr. Aye Maung’s case also demonstrates that the NLD’s professed commitment to federalism is heavy on rhetoric and scant on action. Before being thrown into prison, he was the chairperson of the Arakan National Party (ANP), which enjoys by far the most support among ethnic Arakanese. In the run-up to the 2015 general election, he gave up his position as an MP in the Union Parliament to run for (and win) a seat in the Arakan State legislature, in hopes of leading the state government as chief minister.

Once in power, however, the NLD ignored the political aspirations of Dr. Aye Maung and the ANP by appointing a loyal member of its own party to the chief minister post, thus squandering an early opportunity to build good relations with the ANP and ethnic Arakanese in general. Of course, the 2008 Constitution gives the president — who will inevitably be chosen by the party or parties with a majority vote — the power to appoint chief ministers for all states and regions. However, it would not have been unconstitutional for the NLD to take into account the desire of the ANP, which won the most seats in Arakan State, and make Dr. Aye Maung chief minister. Instead, this early affront set the tone for an NLD-ANP dynamic that has only deteriorated in the years since.

The fact that the NLD formed an ethnic affairs committee at the central level early this year ahead of the general election in November makes clear that their policy of antagonizing ethnic minority groups remains intact. Emblematic of its overarching attitude toward ethnic minorities is the NLD’s “Aung San spree”: not so much in Arakan but elsewhere in non-Bamar areas, the naming of bridges and parks after Aung San Suu Kyi’s father, General Aung San, and erecting statutes of him in several other areas despite staunch opposition from local ethnic populations. Last but not least, proposals that NLD lawmakers made for now-failed constitutional amendments indicate that the party puts its vision of democracy before federalism whereas, for non-Bamar ethnic groups, these two goals are to be pursued simultaneously.

In short, the actions or inaction from the NLD government led by Aung San Suu Kyi in Arakan State show that the party does not care much for the rule of law, nor does it protect what limited political space the undemocratic 2008 Constitution affords. Little of what it has done so far points in the direction of genuine federalism. As one Arakanese MP recently warned after news of Dr. Aye Maung’s electoral disqualification, “This could make the Arakanese public lose their trust in the political and parliamentary paths and push them toward more radical forms of politics.” Even as the party line espouses “political solutions”, the NLD’s self-contradictory and incoherent Arakan State policies are one such push factor.

.jpg)