- Fuel prices triple in Sittwe, forcing some stations to close

- Iran crisis sparks fuel price hikes in AA-held areas

- Arakan residents gripped by fear as junta airstrikes intensify

- Junta personnel, police and families evacuate Sittwe for mainland Myanmar

- Muslim armed groups killed 162 civilians in two years in northern Arakan: HDCO report

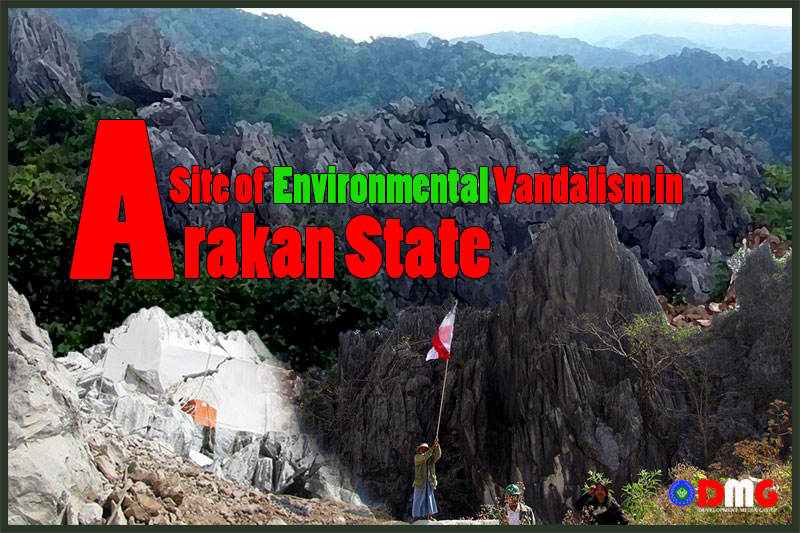

A Site of Environmental Vandalism in Arakan State

From afar, the undiscerning eye sees a majestic mountainscape, where a deep-green forest and sprawling ridgelines covered in mist converge on a majestic peak. But a closer look reveals broken slabs of stone in shades of white, blue and yellow scattered at the foot of the mountain.

06 Feb 2023

Written by Gaung

From afar, the undiscerning eye sees a majestic mountainscape, where a deep-green forest and sprawling ridgelines covered in mist converge on a majestic peak. But a closer look reveals broken slabs of stone in shades of white, blue and yellow scattered at the foot of the mountain.

“The mountain has a pointed peak, and is a gigantic structure,” said Taungup resident Ko Tun Tun, who asked that he be identified by a pseudonym. “The mountain was sawed through. The machine’s blade is over 30 feet long, and slabs were cut out.”

The Nayputaung marble production site stretches for three miles along the rugged mountain road that links up with the Taungup-Pantaung road near the Arakan Yoma mountain range.

“Sheets cut out from the mountain with saws were scattered. They cut out slabs weighing 10 tonnes. When they can’t cut slabs, they cut sheets big enough to be used for making tables. They just throw away pieces that can’t be used at all,” said Ko Tun Tun, recounting what he personally witnessed at the mountain excavation site.

At the time, said Ko Tun Tun observed the hustle and bustle of the marble production operation, with large saw machines and other modern equipment including backhoes and trucks working along the mountain ridge.

Decades of Debate

Successive governments have had their eyes on Nayputaung due to its rare and valuable marble desposits. Myanmar’s first military dictator, General Ne Win, attempted to extract marble from Nayputaung in cooperation with the Japanese government, but his plan failed.

Former President U Thein Sein’s quasi-civilian government signed a contract with Vietnam’s Simco Song Da Joint Stock Co to produce decorative marble stones from the Nayputaung deposits in 2012. According to the contract, 7,850 tonnes of marble would be extracted from the mountain per year for 20 years, beginning in 2013.

Taungup residents, Arakan civil society organisations and environmentalists have continuously opposed the project. Arakan State lawmaker U Aung Mya Kyaw submitted a proposal on March 28, 2013, calling on the government to terminate the project, saying it lacked transparency.

Ko Tun Tun was among the locals who protested the marble quarry, but authorities turned a deaf ear to their demands and pushed ahead with the project.

According to the contract, profits were to be equally shared between the Myanmar government and its Vietnamese partner. The Vietnamese company had agreed to spend 10 to 15 percent of its share of profits on corporate social responsibility projects for local residents, Arakan State mines minister U Aung Than Tin told the Arakan State Parliament under U Thein Sein’s quasi-civilian government in March 2013.

In five years of marble production from 2013 to 2017, about 8,657 tonnes of marble slabs were quarried from the mountain, and some 634 tonnes were exported.

The project was suspended in April 2018 under the National League for Democracy (NLD) government, as it was deemed no longer financially feasible. The NLD’s natural resources and environmental conservation minister, U Ohn Win, in September of that year told the Upper House of Myanmar’s bicameral Union Parliament that the project was suspended due to high production and transportation costs. The project had no access to electricity supplied by the national grid and was being run with diesel generators, he said.

Myanmar’s military regime, however, is planning to revive the project. The junta has again signed an agreement with Simco Song Da Joint Stock Co, and a joint management committee has been formed with four representatives each from the junta’s Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation and the Vietnamese company, according to a regime statement on November 25.

Local communities are again opposing the project.

“This will benefit the military council. But Arakan residents will not receive any benefit from the project. This is a project that has caused huge losses for Arakan residents,” said environmentalist U Tun Kyi.

In the eyes of local people, Arakan State is rich in natural resources, and is among the biggest sources of foreign revenues for the country. They are not happy that despite this, Arakan State is the second-poorest state in Myanmar.

Other projects in Arakan State are also being implemented without the consent of local residents, one being the Shwe natural gas and oil pipelines project, which transports these valuable commodities from the coast of Arakan State to China.

In the aftermath of the coup, the regime is pushing ahead too with a port in Sittwe that is part of the Kaladan multi-modal transit project, as well as the China-backed Kyaukphyu special economic zone (SEZ).

A Mountain Dwindles

“Some 75 percent of the mountain has gone. The environmental impact will be huge. There will be landslides. The ecosystem is damaged,” U Tun Kyi said of the Nayputaung project.

Currently, the military regime is suffering from international economic sanctions, and no doubt views the potential foreign income from the marble production site as a major asset at a time when the junta has seen many revenue streams crimped.

“If this project is restarted, to be used by the military council without any benefit to the people, I see these as undesirable actions,” said U Pe Then, a veteran Arakanese politician.

Critics of ventures like Nayputaung say international investment projects are propping up a regime in survival mode, with revenues in the worst-case scenario going toward the procurement of military equipment to suppress ethnic armed groups and other opposition forces.

DMG attempted, unsuccessfully, to interview Arakan State Minister for Natural Resources U Than Tun and Arakan State military council spokesman U Hla Thein regarding the junta’s push to revive the controversial marble quarry in Taungup Township. Arakan State Minister for Commerce U San Shwe Maung said he was completely unaware of the junta’s plan to restart the mining operation at Nayputaung.

“If the [Union] government develops a project, it has to notify the state government,” U Pe Than said. “Because this project is a resource in Arakan State, it is necessary to be transparent and take into account the negative effects if it is implemented.”

Arakanese environmental activists have lodged some of the most strident opposition to the project.

“If the Nayputaung project is restarted, it could be an incalculable loss for the people of Arakan. The project may result in the loss of the environment and local water resources,” said Ko Myo Lwin, an Arakanese environmental conservationist.

DMG contacted the United League of Arakan and Arakan Army (ULA/AA), which runs an administration parallel to the military council in Arakan State, to ask their opinion about the restart of marble stone production at Nayputaung, but had not yet responded as of press time.

The ULA/AA issued a statement on July 18, 2019, welcoming investments that will benefit Arakan State and work toward the comprehensive development of Arakan State’s security, stability, economy, social and transportation sectors.

Taungup Township residents had hoped that the Nayputaung project would lead to the local manufacturing of finished products in order to provide employment opportunities in Arakan State. They say, however, that only rough marble stones have been transported from the quarry for shipment to Vietnam and other countries, via Yangon.

Article 32 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples states that indigenous peoples have the right to freely decide on the development of their lands and natural resources, and that the government must obtain an agreement with indigenous peoples if they want to carry out projects on natural resources owned by local peoples. But Myanmar’s 2008 Constitution stipulates that the Union has the right to directly manage the natural resources produced by the regions and states, bringing these two documents in obvious tension with one another.

At present, the military junta has not yet explained the project’s benefits, environmental impacts, and pros and cons to the public.

For Ko Tun Tun, the lack of transparency has not prevented him from coming to the conclusion that the cons clearly outweigh the pros.

“About a third of Nayputaung has been demolished,” he said. “However, there are still many marble stones buried in the Arakan mountain range, so I don’t know how much they will extract.”

.jpg)