- Only two Arakan political prisoners freed in junta’s Peasants’ Day amnesty

- Fuel prices triple in Sittwe, forcing some stations to close

- Iran crisis sparks fuel price hikes in AA-held areas

- Arakan residents gripped by fear as junta airstrikes intensify

- Junta personnel, police and families evacuate Sittwe for mainland Myanmar

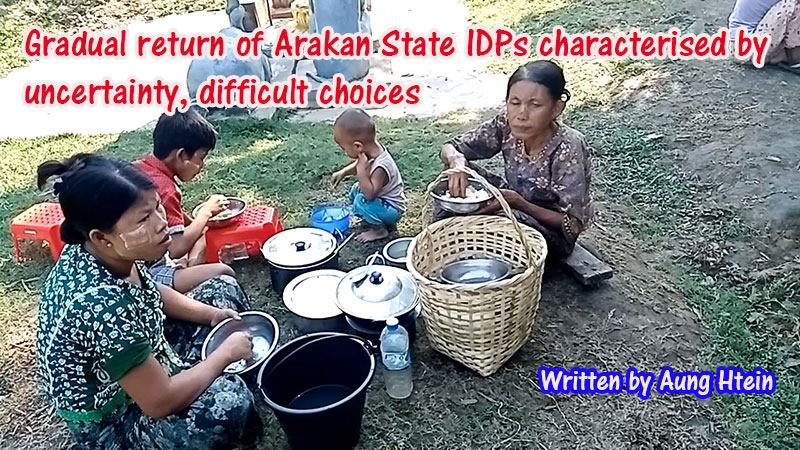

Gradual return of Arakan State IDPs characterised by uncertainty, difficult choices

More than 10,000 IDPs returned home this way in August alone, said an official from the Rakhine Ethnics Congress, a group that collects lists of IDPs in Arakan State.

30 Sep 2021

Written By Aung Htein

It has been more than 10 months without clashes between the Myanmar military and Arakan Army in Arakan State, following an informal ceasefire agreement reached between the two sides ahead of the 2020 general election.

Internally displaced people (IDPs) who fled their homes during the fighting and took shelter in IDP camps are now gradually returning home. However, they are returning home with plans of their own making, not with the help of authorities.

More than 10,000 IDPs returned home this way in August alone, said an official from the Rakhine Ethnics Congress, a group that collects lists of IDPs in Arakan State.

Many of these IDPs decided to return home because they were facing food shortages and joblessness due to the impacts of Covid-19, at the same time that donations to displacement camps have decreased.

Most of the IDPs who have recently returned home are from Kyauktaw, Mrauk-U and Ponnagyun townships, while smaller numbers are also from Rathedaung and Buthidaung townships.

U Hla Kyaw Thar, a resident of Thameehla village in Rathedaung Township who was affected by the armed conflict, said: “My home went up in flames. We do not have money but the family is big. So, we are facing challenges to rebuild our home.”

Hostilities between the Myanmar military and Arakan Army started in December 2018, intensifying in 2019 and 2020.

More than 200,000 people in Arakan State were displaced during the conflict, while many civilians including children were killed. Multiple villages near or in the midst of the armed conflict were torched and/or deserted.

In some cases, entire life’s savings were lost. Displaced families have found themselves crammed into tiny, single-room dwellings at IDP camps, dependent on food donated by humanitarian aid groups.

Relief aid from foreign and domestic donors arrived to IDPs regularly in pre-pandemic times, but following the spread of the virus and Myanmar’s February 1 coup, insufficient food supplies have been a frequent concern at displacement camps.

Amid such conditions, many IDPs have decided to return home, according to U Zaw Zaw Tun, secretary of the Rakhine Ethnics Congress.

“The current difficulty for them to return home relates to accommodation and food. They need to repair their houses. They need to hunt for a job near their area to get income for their living. They decided to return home although the situation is not ready for them because the conditions living at IDP camps are worse,” U Zaw Zaw Tun said.

More than 100,000 IDPs have returned home since the fighting stopped in Arakan State, but some 90,000 people remain displaced.

One home return that has been in limbo for months involves the residents of Tinma village in Kyauktaw Township, where around 200 houses were burnt down and hundreds of people were displaced.

An agreement was reached between the Arakan State Administration Council and the Tinma villagers on June 24 to ensure the safe return of those displaced, but the council has been slow to implement the agreement, the villagers have said.

The villagers have asked the military government to clear landmines and rebuild houses ahead of their return, but their demands have not yet been met.

“We want to return to our home. We do not want to stay living this life, struggling with the various challenges as an IDP. We want to work in our village for our living. The difficulty here [as IDPs] is not suitable for us in the long term,” said U Saw Thein, a resident of Tinma village.

Underpinning the uncertainty for IDPs is the lack of a formal ceasefire between the military and Arakan Army. For both IDPs who have returned home and those who have yet to do so, there are persistent worries about the possibility of fresh clashes between the previously warring sides.

U Pe Than, a former Pyithu Hluttaw lawmaker from Myebon Township, said it is important that both sides continue to refrain from gunfire so that IDPs can live and work peacefully in their respective towns and villages.

“IDPs [hesitate to] return home because they are considering whether there is a viable livelihood in their villages. The situation depends on whether fighting breaks out or not. They can return home when there is a situation that is completely viable for them. Such a situation can be guaranteed after the government and AA sign an agreement to make peace,” U Pe Than said.

There is little doubt that those IDPs who choose to return home face formidable challenges as well, rebuilding their homes and villages. The risk of landmines and unexploded ordnance looms large in conflict-affected areas, and there are numerous hurdles to resuming the paddy cultivation that is the backbone of most rural economies.

Indeed, rehabilitating the lives of IDPs who now seek to return home involves addressing many challenges before they might even get back to a place they once were, let alone move forward.