- Clashes continue in Sittwe as junta reinforces naval, armored deployment

- Arakan Army signals willingness to forge strategic partnership with Bangladesh’s new government

- Internet blackout in Arakan State hampers emergency aid delivery

- Arakan residents call for air raid warning systems amid surge in junta airstrikes

- Arakan’s Breathing Space (or) Mizoram–Arakan Trade and Business

Searching for Union Spirit in Arakan at Independence, and Today

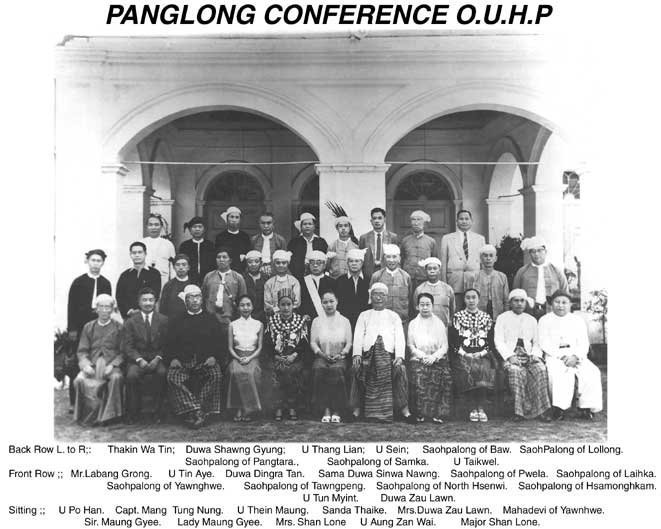

U Aung Zan Wai was also the only Arakanese politician who travelled to Panglong for the forging of the Panglong Agreement in 1947. In Arakan politics, there was a parliamentary grouping, led by the former Prime Minister Sir Paw Tun on the nationalist right. Then, on the left, the armed Arakan People’s Liberation Party was established by the leadership of U Seinda in November 1945.

04 Jan 2021

By Kyaw Lynn | DMG

When the Arakan Army attacked four border guard police stations in Arakan State on January 4, Myanmar’s Independence Day, in 2019, most Bamar politicians and political analysts criticised the action as an assault on the country’s sovereignty and independence. However, the AA’s vice commander Dr. Nyo Twan Awng replied that the operation unintentionally coincided with Independence Day and that, “The war does not see Independence Day or weekends.” Intentional or not, this insurgent military attack highlighted the born deficits of Myanmar independence and its betrayed Panglong promises, to which the Burma Proper government’s leader, General Aung San, and Kachin, Shan and Chin national leaders had agreed.

Arakan and the Panglong Story

The Panglong Agreement was signed on February 12, 1947, with the aim of union between Burma Proper and the Frontier Areas where non-Bamar ethnic people resided. The accord’s main promises were to grant full internal self-autonomy, to adopt resource-sharing arrangements, and to guarantee the democratic rights of the Frontier Areas and their peoples.

Arakan was not a priority for Bamar leaders in their union-building project because it was not even a separate territory at that time, and possibly was not even considered to be inhabited by a distinctive people in the eyes of Bamar leaders. U Aung Zan Wai, an Arakan National Congress leader and later an Anti-Fascist and People Freedom League (AFPFL) executive member, finally recalled that the cooperation with the AFPFL did not promote Arakan national unity; rather, it led to increasing interference of Ministerial Burma’s political interests in Arakan.

U Aung Zan Wai was also the only Arakanese politician who travelled to Panglong for the forging of the Panglong Agreement in 1947. In Arakan politics, there was a parliamentary grouping, led by the former Prime Minister Sir Paw Tun on the nationalist right. Then, on the left, the armed Arakan People’s Liberation Party was established by the leadership of U Seinda in November 1945. Only in April 1947, an Arakan Leftist Unity Front was established at an “All Arakan Conference” in Myebon initiated by U Seinda and the local Red Flag Communist Party of Burma (CPB) leader Bonbauk Tha Kyaw. U Aung Zan Wai and his ANC’s political stance were at the centre compared with these two political blocs.

While Kachin, Shan and Chin leaders were promised full internal self-autonomy in their respective states, Arakan political parties like the Arakan National United Organization (ANUO) were struggling to secure for Arakan equal status as a “State”, as other ethnic groups were achieving in the post-independence political arena. Prime Minister U Nu at that time did not agree with the formation of Arakan State on the grounds that he viewed Arakanese people as not worthy of possessing a unique state, separate from the Bamar mainland, due to religious and cultural similarities. Only in the 1960 election campaign, he started to support the creation of new Arakan and Mon states, mainly due to his political interests, because he wanted his Clean AFPFL faction to have more popular support than the Stable AFPFL.

A Muslim Minority

For Muslims in Arakan, the main political force was the Burma Muslim Congress (BMC), which was established as an affiliate of the AFPFL in December 1945 to show their support for the national independence struggle. Its main strategy was also working together with the Bamar-centred AFPFL and this way was also supported by most Muslim conservatists in Arakan. But more radical voices made three demands: the independence of the Mayu frontier region; an autonomous region that would be part of either Arakan or the new Union; the conjunction of Muslim-majority territories in northern Arakan to the new state of East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). None of those ideas was successful.

However, with the rise of ethnicised politics in the post-war period, Muslim leaders quickly realised that they needed a “nationality” of “statehood” so that their voices could be effectively recognised. In April 1947, a call for an Islamic Frontier State was declared at a mass meeting of the Jamiatul-Ulama in Maungdaw. Then, in the Dabbori Chaung Declaration, Muslim leaders had also called for the formation of a Muslim autonomous state between the Kaladan and Naf rivers in August of that year. After that, the “Mujahid Party” was established by the lead of popular singer Jafar Kawal (Jafar Hussian) and hundreds of supporters near Buthidaung at around the time of Burma’s independence. In 1949, the Mujahid Party took control of much of the former Mayu frontier region in the far north of Arakan. But the Burmese military’s “Operation Monsoon” was able to capture the Mujahids last strongholds along the Naf River frontier in 1954.

Still, minor insurgent movements were continuing around the Mayu Range. In terms of electoral politics, Muslim candidates also won in the constituencies of Maungdaw and Buthidaung with the support of Jamiatul-Ulama and sometimes the Burma Muslim Congress in the 1947, 1951 and 1956 elections. Most conservative Muslims, on the other hand, also disagreed with the Mujahid armed struggle, and some Muslim politicians even attempted to convince the Mujahids to lay down their arms so that the government could consider the latter’s political demands. However, these Muslim politicians also rejected cooperation with ANUO leaders to form an “all Arakan” alliance that could press for Arakan statehood. Rather, their main strategy was to press central Burma’s political leaders to achieve the rights of the Muslim population in northern Arakan.

However, at the last, it seems that none of the political forces in Arakan achieved their ultimate aims during the parliamentary period, and their political movements were also massively set back by the military coup led by General Ne Win in 1962.

Throughout the parliamentary period (1949-62), the political centre of Burma was Rangoon and its most difficult political issues were communism and ethnic armed struggles, and the Kuomintang invasion into Shan State. The centre of the communist armed revolution was the Bago Yoma and Burma Proper areas, and the main ethnic armed force at that time was the Karen National Union (KNU), which mainly operated in areas where ethnic Karen resided, in Burma Proper’s Irrawaddy Delta region and (what we today call) Karen State and its surrounding lands.

Arakan at that time was not an area of focus for the Rangoon government and its anti-insurgency efforts. But Arakan today is the source of two of the most important political issues facing the country: the armed struggle of the Arakan Army, and the question of the Muslim community in Arakan. At this point, the Myanmar government needs policy flexibility to solve both of these political issues in Arakan effectively.

Two Birds With One Stone

The main Arakanese armed organisation today is the Arakan Army/United League of Arakan (AA/ULA), which is a member of the Federal Political Negotiation and Consultation Committee (FPNCC) politically, and of Northern Alliance militarily. The FPNCC has demanded an alternative path to the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) framework, and still includes the country’s most powerful ethnic armed organisations, like the United Wa State Army (UWSA), Kachin Independence Organization (KIO) and Shan State Progressive Party (SSPP).

Some political analysts have estimated that the number of troops possessed by FPNCC members is not less than 70% of all non-state forces. That means the political gravity of non-NCA forces seems to be more attractive than the NCA signatories, and the question of recognising the existence of the Arakan Army in Arakan is also a key issue that FPNCC members should wish to solve collectively. The armed struggle of the Arakan Army also has no clear way to de-escalate and resolve without taking their political demands to the peace table.

On the other hand, the Myanmar government is also facing huge international pressure over its inability to solve the Muslim issue in Arakan effectively. Although the issue was mostly viewed and claimed as a domestic affair under the former U Thein Sein government, it has become more and more pronounced regionally and internationally under the current de facto leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s government.

The two main political issues in Arakan are fundamentally different in terms of principles at stake, since the AA revolution is about a demand for collective rights, whereas the Muslim issue is about the right to citizenship. Still, both the Myanmar government and the international community should care about the interconnection of these two issues on the ground. Practically, the Muslim issue will still be very difficult to solve until the AA’s political demands are satisfied, which are to change the political system of Arakan as a whole. The northern parts of Arakan are currently the epicentre of the AA armed revolution, the Muslim issue and multiple attendant humanitarian crises. It will demand strategic agenda-setting to solve these two issues step by step.

At first glance, the rise of the Arakan Army and Arakan nationalism could be viewed as a threat to the existence of the Muslim community in Arakan, but in reality the situation has gone in a different direction of late, meaning the perceptions of most Arakanese people now have changed in a positive direction compared with 2012. This could be due to three main factors: 1) Arakanese people themselves now face a mass humanitarian crisis, like the Muslim community has; 2) Both Arakanese and Muslim communities now understand that they are under the same oppressor; and 3) Nationalism promoted by the Arakan Army is more than Arakan (Rakhine) ethnonationalism, and is more like a geographic or Arakan nationalism, in which diversity of religions and ethnicities is welcomed.

With that said, and given the increasing AA/ULA dominance in Arakan and its pluralist political principles, the AA/ULA should also be considered as one of the key stakeholders in solving the Muslim issue in Arakan in the future. To pave the way for that, a change in the political system so that the AA/ULA can have more robust and legitimate participation in Arakan is the most realistic way to kill two birds with one stone.

About the Author: Kyaw Lynn is a post-graduate student mastering in political science at the University of Yangon, as well as a freelance political analyst. He is also one of the founders of the Institute for Peace and Governance (IPG).

.jpg)