- Children in Arakan State face rising cases of pneumonia and flu

- Muslim militiamen flee junta camps in Sittwe amid oppression, discrimination

- Junta navy activities halt fishing in Thandwe

- Junta airstrike kills 21 POWs, family members at Kyauktaw detention centre

- Arakan Army seeks to expand territorial control in Sittwe

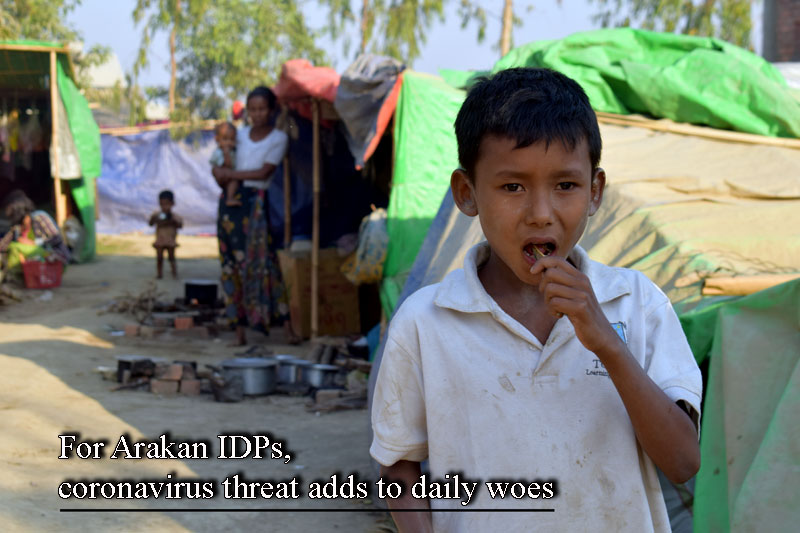

For Arakan IDPs, coronavirus threat adds to daily woes

With increasing numbers of people forced to flee their homes and civilian casualties continuing to mount, for many there is little time to ponder COVID-19’s deadly march across the world. It is not that they live without fear of the pandemic, but rather that their fear is tempered by limits on the amount of information they receive about it, and its relative place in the hierarchy of numerous daily concerns to be paid heed.

09 May 2020

By Nay Myo Lin and Khin Tharaphy Oo

As is the case in several other parts of Arakan State, fighting between the Arakan Army (AA) and the Myanmar military has produced thousands of internally displaced people (IDPs) in Ponnagyun Township this year.

With increasing numbers of people forced to flee their homes and civilian casualties continuing to mount, for many there is little time to ponder COVID-19’s deadly march across the world. It is not that they live without fear of the pandemic, but rather that their fear is tempered by limits on the amount of information they receive about it, and its relative place in the hierarchy of numerous daily concerns to be paid heed.

According to the Ministry of Health and Sports, there are currently 176 confirmed COVID-19 cases in Myanmar, with six people dying from the disease. Despite there not being even a single reported case in Arakan State thus far, people here are concerned about the dangers of coronavirus, especially for those who have had to flee their homes.

There are currently more than 160,000 people displaced by fighting between the Tatmadaw and the AA, the majority staying in townships under internet restrictions imposed by the government. As a result, many people in Arakan State have limited access to information concerning COVID-19, which has dominated headlines from New York to New Delhi for months.

A camp in Zedipyin village, Ponnagyun Township, currently houses 1,200 displaced people. One camp resident, 24-year-old Ma Nyein Chan Myaing, said she did not have accurate information about the virus, nor was she clear on how it was transmitted nor how to avoid it.

The internet ban means government information and announcements are unavailable through online channels. Many people in the camps, having fled their homes with nothing but the clothes on their backs, don’t have radios, TVs or access to newspapers.

Phone calls with relatives and friends in other regions and countries can be a source of information about the virus. Some say the only news they’ve heard about COVID-19 is from people who have returned from urban areas, and who say without embellishment that it’s a “dangerous disease.”

“We simply don’t have access to information,” said U Thu Wanna Sekka, a monk who spoke with DMG and is in charge of the Zedipyin camp.

While he disseminates knowledge about the virus to some IDPs, most have not yet received any information. So far no steps have been taken by the government or civil society groups to widely share information among displaced populations about virus transmission and how people can protect themselves against it.

“We need to be shown how to protect ourselves against this disease,” Ma Nyein Chan Myaing explained.

Unfeasible advice

The COVID-19 protection guidelines issued by the Ministry of Health and Sports include advice such as, “Stay at home as much as you can. Avoid crowded places. Wash your hands frequently with soap and water for 20 seconds. Only communicate with others who are at least 6 feet away.”

Although these messages are slowly getting through to the IDPs, the advice in the guidelines is often impractical, given the conditions in the camps. At the Zedipyin settlement where Ma Nyein Chan Myaing lives, 10 people or two to three families had to live together per room.

“Avoid crowded places,” the Ministry of Health and Sports insists. Yet at night, people sleep lined up side by side, and during the day spend much of their time crammed together. Crowds of people pack together during food distributions.

Frequent and thorough handwashing is important to prevent the spread of the virus, yet water scarcity means this is unrealistic. Water was in short supply during the first week of April at the Zedipyin camp, just days after Myanmar reported its first confirmed coronavirus cases.

To boil rice, wash clothes and bathe at Zedipyin camp, people must walk to fetch water from a well 2 miles away from the village. People are limited as to how much water they can take, with just 2 gallons of water permitted per day.

The well is also located in an area where fighting has recently taken place, and people are afraid of being shot at if walking alone or in small groups. Many will only go if they can travel as a large group. Water is also difficult to carry, and so generally, IDPs complain that after meeting their drinking water needs and cooking, there isn’t enough to spare to frequently wash one’s hands.

If there is to be any hope of staving off a potentially devastating coronavirus outbreak in one or more of Arakan State’s IDP camps, the government and civil society organisations would be well-advised to provide water for drinking and sanitation purposes as needed.

Face masks and soap are also in troublingly short supply. In the Zedipyin camp, facemasks are scarce or, as Ma Nyein Chan Myaing contends, non-existent. “I’ve never seen a mask,” she said. “They don’t sell them in the village.”

Combating COVID-19 amid a war zone

Civilians continue to be shot and otherwise killed and wounded as fighting in the northern townships of Arakan State rages on. Civilians and government employees face arrest by armed groups on both sides of the conflict.

While education sessions about coronavirus have been held in some camps, it is often difficult for those organising the sessions to travel to these areas, according to Arakan State Social Welfare Minister Dr. Chan Thar, who spoke with the media on March 23.

“It is really sad seeing the people living in the camps; they’re living in cramped conditions. We have difficulties travelling there to provide education sessions for them,” he said.

There has been criticism of the authorities for providing little in the way of education concerning the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in the camps in rural areas. Education sessions have been mostly limited to camps based in or near towns, according to Ko Zaw Zaw Tun, secretary of the Rakhine Ethnics Congress (REC).

Some civil society organisations understand that the government’s inability to provide education sessions to displaced populations in rural areas is due to security. Zaw Zaw Tun suggested that civil society groups should be welcomed to cooperate and work together to provide education to IDPs if government personnel are unable to do so by themselves.

“They say we can’t go for security reasons. Instead of saying that, we have to find out who can do it if we can’t,” he said.

The problems at IDP camps are numerous and varied. Some solutions seem distant or unattainable, while others are eminently doable — with sufficient political will.

One fix is literally without cost: To help educate people in the camps about how the virus is spread and how to avoid it, the internet ban could immediately be lifted, opening up the information superhighway to mobile phone users.

Other measures would require funding. Zaw Zaw Tun says more adequately spaced living quarters should be built to alleviate crowding, and food supplies and other items to ease the burdens of daily life are required.

In the COVID-19 era, when everything for everyone can feel disrupted, it’s important to remember that these IDPs have had to abandon their homes and often lack life’s basic necessities. For them, the coronavirus threat looms overhead, but it is just one of many existential challenges they face.

Originally from Pauktaw Pyin village, Ma Nyein Chan Myaing summed things up this way: “I want to encourage the government and civil society organisations to consider these issues before our lives are put at risk. We need to be supported.”