- Over 1,600 students sit for matriculation exams in three regime-held townships in Arakan State

- DMG Editorial: The Military Junta Is Openly Killing Its Own Soldiers in a Revolting Act

- Merchants struggle under NUG fuel transport restrictions in Arakan State

- Nearly 500 flee homes after junta airstrike on POW detention site in Ann

- Fuel prices double in Arakan Army-held areas amid panic buying

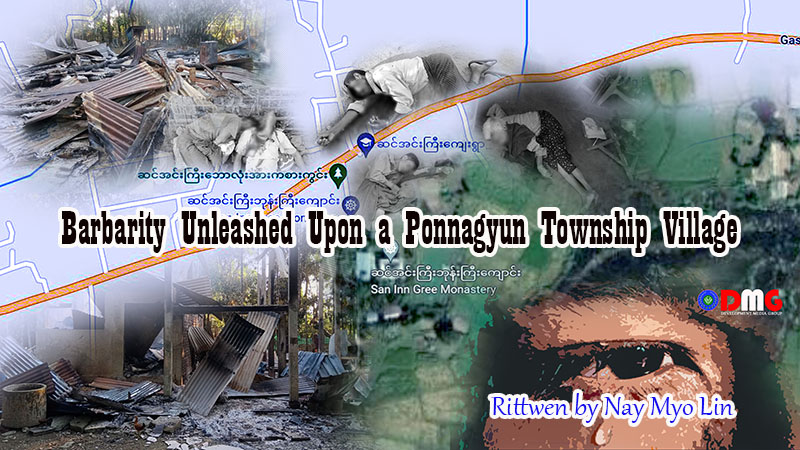

Barbarity Unleashed Upon a Ponnagyun Township Village

The ambush was followed by retaliatory artillery barrages from the military’s Ponnagyun-based Light Infantry Battalion No. 550 and air strikes by junta helicopters near the two villages. And a junta column marched toward Sin Inn Gyi Village, which is located along the Sittwe-Yangon road.

24 Nov 2022

Written by Nay Myo Linn

Faced with the dilemma of whether to wait for her husband who had entered the burning village or flee with their three children, Daw Ma Mya Thein made a reluctant decision to choose the latter, for the safety of their children. She made a call to her husband U Maung Maung Thein before she fled, but he didn’t answer his phone. This greatly worried Daw Ma Mya Thein, whose name has been changed for this story.

It was around 6 a.m. on November 10 when local residents heard loud explosions emanating from somewhere between Sin Inn Gyi and Padetha villages in Ponnagyun Township. Residents would later learn that the Arakan Army (AA) had ambushed a junta vehicle that was transporting food supplies along the Yangon-Sittwe road.

The ambush was followed by retaliatory artillery barrages from the military’s Ponnagyun-based Light Infantry Battalion No. 550 and air strikes by junta helicopters near the two villages. And a junta column marched toward Sin Inn Gyi Village, which is located along the Sittwe-Yangon road.

Villagers were initially relieved when the military column turned back before reaching Sin Inn Gyi, but for reasons unknown, the soldiers returned a few hours later.

Many Sin Inn Gyi villagers fled to the monastery outside the village with only the clothes on their backs. Elderly residents were left to take care of their homes.

“We thought they would not do anything to elderly persons, and that they would listen to us if we spoke to them gently, so we stayed,” said the brother-in-law of U Maung Maung Thein.

By 5 p.m. on November 10, junta troops were in the village. Clouds of smoke rose into the sky a few minutes later. One villager came running from the village and shouted, “Two houses have been torched!”

Together with fellow villager U Maung San Hla, U Maung Maung Thein decided to go back to the village to check up on their houses and those of their neighbours. Other villagers tried in vain to dissuade the pair from going back, but away they went, amid the sound of continuous gunfire.

“We have not been able to call his phone since,” said Maung Maung (also a pseudonym), the 18-year-old son of U Maung Maung Thein, sobbing.

Daw Ma Mya Thein was concerned for her husband’s safety, as were other villagers as they could hear gunfire from the village, which they could see was burning.

The regime troops left the village at around 7 p.m. But none of the villagers taking shelter at the monastery dared to return to the village that night. When they went back to the village the next morning, they found several lifeless bodies bearing signs of multiple wounds.

“We saw two bodies as we entered the village,” said a Sin Inn Gyi resident who asked for anonymity out of fear for his safety. “They were apparently forced to sit. Their bodies were in a sitting position. One of the bodies was lying face down, and the other was lying face up. They were apparently shot in their throats. Their throats were covered in blood.”

The villager continued: “As we made our way farther into the village, we saw another body on a concrete path who was apparently shot while fleeing. As we moved forward to the east of the village, we saw two more bodies, who were also apparently shot while fleeing. We also found two women and a man dead outside a house. There was another body that I didn’t see.”

U Maung Maung Thein was one of those found shot dead in Sin Inn Gyi Village. Eight other people were killed that day, ranging in age from 38 to 92 years old. Seven houses in the 120-household village were burnt to the ground, and rice stored for consumption was also reduced to ashes.

U Maung Maung Thein’s son said he grieved not only the loss of his father, but also their home.

“We are still young. Without my father, it’s like an arm has fallen off,” he said.

U Maung Maung Thein is survived by three sons, the eldest 18 and the youngest just 2 years old.

His widow, left to face the simultaneous loss of her husband and the family home, said she was “suffering a lot” and declined to give an interview to DMG.

“My mother is still in tears since my father died,” said Maung Maung. “I haven’t shown the photo of my father’s death to my mother and younger brothers for fear that something will happen to them.”

U Khin Maung and Daw May Nu, a married couple, were found dead inside their home, said Ko Thein Maung, the younger brother of U Khin Maung. In deciding to stay in Sin Inn Gyi, the couple underestimated the junta soldiers’ cruelty, telling themselves, “They would not harm the elderly in the village.”

“Their children were sent to another location in the morning for fear of being harmed by the junta soldiers,” Ko Thein Maung explained.

Their children survived the danger, but the couple did not. Pain, anger, and sadness are what their deaths have caused for U Thein Maung, who said he believes that those who perpetrate this inhumane massacre will also be punished one day.

Myanmar’s military and the Arakan Army reached an informal ceasefire agreement ahead of the country’s November 2020 general election, after approximately two years of often-intense fighting in Arakan State. The peace pact has since broken down, however, with more than 17,000 civilians newly displaced as a result.

The ceasefire did not last long as the Arakan Army’s continuous push for the liberation of Arakan State ran up against the Myanmar military’s unyielding adherence to its principle of “non-disintegration of the union.”

Prior to the breakdown of the truce in August, the Arakan Army had expanded its administrative machinery in Arakan State and also made inroads on the establishment of a separate, parallel legal system in the state. There is little doubt that the growing influence of the Arakanese armed group contributed to the informal ceasefire’s demise.

The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) said that with those newly displaced, the total number of IDPs from past and present military-AA fighting stood at more than 91,000 as of October 19. Artillery strikes both related to clashes and unprovoked have hit several villages in the weeks since, displacing many more — including thousands affected by the events of November 10 in and around Sin Inn Gyi and Padetha villages.

Most residents of Sin Inn Gyi Village have fled to displacement camps in downtown Ponnagyun and neighbouring Yoetayoke Village. The razed homes remain piles of ash and the surrounding paddy fields are yellowing, but there is no one in the village to clean up the mess or harvest the rice.

“I feel sorry for the people who were killed,” Ko Thein Maung said. “There will be people who will retaliate against the people who brutally killed those nine people. The people who brutally killed the nine people should get worse punishment.”

.jpg)