- Arakan Army signals willingness to forge strategic partnership with Bangladesh’s new government

- Internet blackout in Arakan State hampers emergency aid delivery

- Arakan residents call for air raid warning systems amid surge in junta airstrikes

- Arakan’s Breathing Space (or) Mizoram–Arakan Trade and Business

- Death toll rises to 18 after junta airstrike on Ponnagyun village market

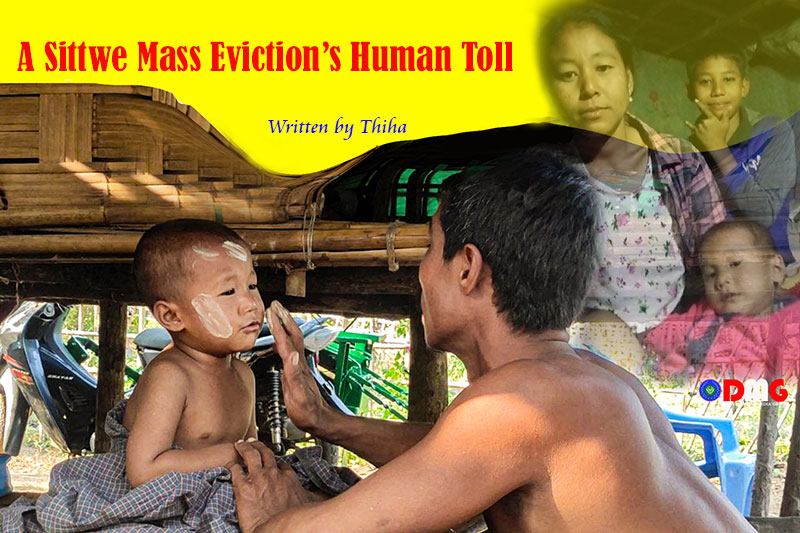

A Sittwe Mass Eviction’s Human Toll

“After I die, take care of our children like I have done. Don’t remarry. I will keep an eye on you by the railroad,” 34-year-old Ma Aye Htwe Yi told her husband Ko Twan Oo Kyaw earlier this month, not long before she departed this life.

27 Mar 2022

Written by Thiha

“After I die, take care of our children like I have done. Don’t remarry. I will keep an eye on you by the railroad,” 34-year-old Ma Aye Htwe Yi told her husband Ko Twan Oo Kyaw earlier this month, not long before she departed this life.

Hers is one of the many families victimised by armed conflict in Arakan State. They moved to the Arakan State capital Sittwe from Mrauk-U in 2020, fleeing clashes between the Myanmar military and Arakan Army at the time.

They lived in Set Yone Su ward in the early days after settling in Sittwe. They lived a hand-to-mouth existence.

“There were days when we could only feed our children and we had to eat their leftover rice with a few peppers and salt,” said Ko Twan Oo Kyaw.

In November 2020, they bought a land plot for K100,000 near the railroad in the west of Mingan ward, and moved into their new home not long after.

The family faced various difficulties during the Covid-19 crisis.

“I had no job and no income because of Covid-19 and political instability. But we still managed to scrape by, and pretended that we were fine while we were in fact going hungry,” recalls Ko Twan Oo Kyaw.

After moving to the new house near the railroad, they welcomed a new member to the family with the birth of their third son. Then on February 12 of this year, Myanma Railways (MR) staff came to their house and others around them, and conducted headcounts. They were not given a reason for the tallying.

An eviction notice arrived at their home two weeks later, and it was entirely unexpected. The notice said they were living on MR-owned land, and would be forcibly removed if they did not voluntarily leave within five days. Ko Twan Oo Kyaw read the notice to Ma Aye Htwe Yi, who was illiterate.

“I was shocked when I got the notice. I tried to hide it, but she saw it and asked me to read it,” said Ko Twan Oo Kyaw.

From that day forward, Ma Aye Htwe Yi became increasingly listless, even refusing to eat.

“When she told me to take care of the children like she does, I even told her not to imagine such nonsense” as her not being there to care for them, he said.

At around 1 a.m. on March 4, Ko Twan Oo Kyaw was woken by his groaning wife. As he sought to help her, he noticed that she had taken poison, and rushed her to Sittwe General Hospital.

“My husband is innocent,” Ma Aye Htwe Yi told the medics before she was taken into the emergency room, for fear that Ko Twan Oo Kyaw would be suspected of poisoning her, adding that he was a good husband and that the couple had never had a fight.

“The doctors told me that when they asked her why she had taken the poison, she said she was so depressed that she’d decided to take her own life,” said Ko Twan Oo Kyaw.

With her health deteriorating even while receiving treatment, Ma Aye Htwe Yi sought her husband’s forgiveness for poisoning herself, and asked Ko Twan Oo Kyaw to bring their sons to her bedside. Her weary eyes rested on them, and she patted their heads. Then blood trickled from Ma Aye Htwe Yi’s mouth and nose, and she took her last breath in Ko Twan Oo Kyaw’s embrace.

“Before she died, she kissed me on my cheek. She told me that she was wrong and asked me to forgive her and take care of our three sons,” he said.

Less than a week after Ma Aye Htwe Yi died, military, police and governmental personnel began removing the homes of those they considered to be “squatters” near the railroad.

Seventy-nine families, including Ko Twan Oo Kyaw’s, appealed to the Arakan State Administration Council not to have their homes demolished, but to no avail.

Friday, March 11, was the day that the home of Ko Twan Oo Kyaw and his now-motherless family was demolished. Ko Twan Oo Kyaw said he stood on the train tracks and watched as authorities destroyed their house.

“I knew that if I had demolished my home, some things could be saved, but I did not have the courage to demolish my own home,” said Ko Twan Oo Kyaw.

The Arakan State regime council has since resumed train service along the Sittwe-Yaychanpyin rail route, and “squatters” living near the tracks were removed, acknowledged Police Colonel Thet Lwin, who is the state’s transportation minister.

Most of these people are now homeless. Ko Twan Oo Kyaw and his family, who are among the dozens of families who have lost their homes, are currently living in a small house in Sittwe’s Set Yone Su ward. For now they live there for free, with the help of a friend.

“The home is advertised to be sold. We are allowed to live in this home because the home is not sold yet. I don’t know where we will live when the home is sold,” he adds.

Ko Twan Oo Kyaw and the three children have not forgotten their mother. The boys range in age from 2 to 15 years old. This single father makes a living as a three-wheeled motorbike driver in Sittwe. His earnings go toward supporting the upbringing of his three sons.

For the youngest, some of the money is used to buy dried milk powder — something the toddler’s late mother can no longer provide.

.jpg)