- Over 1,600 students sit for matriculation exams in three regime-held townships in Arakan State

- DMG Editorial: The Military Junta Is Openly Killing Its Own Soldiers in a Revolting Act

- Merchants struggle under NUG fuel transport restrictions in Arakan State

- Nearly 500 flee homes after junta airstrike on POW detention site in Ann

- Fuel prices double in Arakan Army-held areas amid panic buying

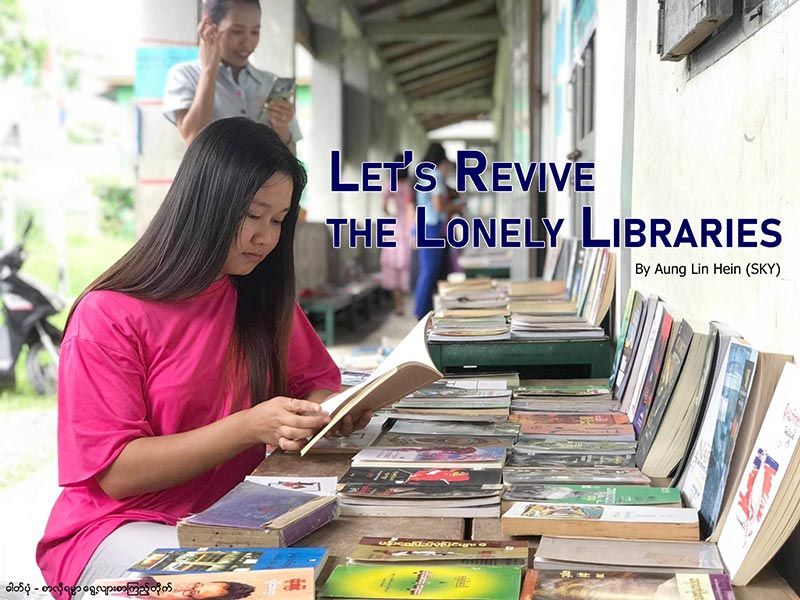

Let’s Revive the Lonely Libraries

While visiting Japan in 2016, I had the opportunity to visit Sendai Mediatheque in Sendai, Japan. I envied the Japanese people reading in this magnificent library, media and art space. Japan is notorious for its long-hours work culture. Surprisingly, many Japanese still find time to read and study books and literature. I remember seeing young and old alike sitting in the library, and imagining a time when libraries in our country would be like Japan’s.

01 Jul 2021

By Aung Lin Hein (SKY)

Libraries have been lonely for a long time, and we have often abandoned libraries. Behind their walls and locked doors, libraries are tired of waiting for readers. Every time we pass in front of the libraries, the libraries look at us like innocent prisoners at the prison window, waiting for us like a child waiting in the alley for the return of mom and dad.

These days, “book culture” is being revived with mobile libraries in rural villages and towns, an initiative spearheaded by young people. Mobile libraries came to life as brick-and-mortar libraries became lifeless; a rebirth for survival. As young people try to keep libraries from being lonely, reading enthusiasts are starting to recreate opportunities to read books. Ma Thandar Kyaw Zaw aka Ma Thandar and others started the mobile library in Sittwe. Since 2008, they have been opening mobile libraries in some Arakan State townships under the name “Waterfall Mobile Library,” as well as helping libraries in rural areas.

Recently, Green Sittwe in the Arakan State capital has launched a library campaign for book lovers under the name of Sarpay Laynyin. Mobile libraries were opened in Mrauk-U, Kyaukphyu, Buthidaung, Rathedaung, Ponnagyun, Minbya, Ramree and Kanhtaukgyi townships with the leadership of Arakanese youths. I personally attended the opening of a youth-led youth library in Myebon Township last winter.

Those who want to create mobile libraries have to collect books, attract readers and find book donors. Young people need to use their brains to find literature that is relevant to their readers. As young people seek new innovations for mobile libraries, making them eager to read may be the hardest part, and they need to be prepared for long-term sustainability.

Ideally, young and old alike will meet in mobile libraries created by young people, where they can read and share books. The bookworms can enjoy coffee at the mobile library and recite poems. Reading enthusiasts will talk to poets and writers about the seriousness of literature. Young people will create more people who want to read. We need to build knowledge banks that are open to all, regardless of party affiliation or religion.

The creation of mobile libraries for young people is being promoted to increase readership as existing libraries become obsolete. Each nation has its own literary, musical, and cultural characteristics. History proves that literature has flourished in Arakan State since ancient times.

It is not only developed countries that focus on reading and writing. Both rich and poor nations hold up their literature, and writers are often recognised. The more readers you have, the more mature your thinking and the higher your sense of knowledge.

While visiting Japan in 2016, I had the opportunity to visit Sendai Mediatheque in Sendai, Japan. I envied the Japanese people reading in this magnificent library, media and art space. Japan is notorious for its long-hours work culture. Surprisingly, many Japanese still find time to read and study books and literature. I remember seeing young and old alike sitting in the library, and imagining a time when libraries in our country would be like Japan’s.

In 2015, I also visited the University of Santo Tomas, the oldest existing university in Asia, in downtown Manila, Philippines. I was thrilled to see students reading books and doing research at the university. On the other hand, I was deeply saddened remembering Myanmar’s history of university students arrested on political charges. Imprisonment of students — the country’s future leaders — is not over yet.

As far as I know, veteran writers say that the early days of libraries in Sittwe date back to around 1970. But libraries disappeared after 1988. In practice, freedom of the press and freedom of speech have been restricted for decades, and there have been dark times during which readers have been deprived. Prospective writers and readers have gradually moved away from books and libraries, with an emphasis on family livelihoods due to extreme poverty.

The people of Arakan State, who have been struggling with more than a decade of war, ethnic conflict, natural disasters, epidemics and economic hardship, have found it impossible to spend more time on literature. For much of the past three years, artillery shells have exploded, and entire villages have been reduced to ashes, including their libraries.

Around 2003, when I passed the matriculation exam, while studying English I had access to a language center called the Millennium Center in Sittwe, where I could read and rent good English books. But the library collapsed prematurely due to poor management. Now, the Golden Pagoda Sayadaw has opened the library again at the Golden Pagoda Monastery.

I would like to urge those who write books and those who set up libraries to do things that others cannot do, and learn from past failures. Parents and guardians themselves are addicted to social media at the expense of reading books, and it is important to tell their children not to overuse their phones.

Instead, it is important to use social media and mobile phones as tools to increase the desire to read and study. There are other reasons for optimism: Donations of books and literature are still being made by philanthropists and writers themselves. There are still people who have their own home-based libraries.

After I entered the world of journalism in 2007, I collected gifted journals and set up reading rooms in my neighbourhood with the help of an uncle next door. One of the places that led to the revitalisation of these community reading circles was the ‘Open’ library under a banyan tree near Pho Thar village in Sittwe Township. Similar reading circles are now being found in other townships’ villages.

Libraries are, in fact, knowledge banks and the foundations for a better future. They are a resource centre for the reading of books and other literature, and for the continuous development of good people who will lead in the future. It is never too late to make a positive change. Let’s revive the lonely libraries for the betterment of the nation.

.jpg)