- Extreme poverty drives Sittwe residents to dismantle abandoned houses for income

- Weekly Highlights from Arakan (Feb 23 to March 1, 2026)

- Over 300 political prisoners freed from 10 prisons nationwide

- DMG Editorial: Between War and Opportunity - A New Border Reality for Bangladesh and Arakan

- Arakan Army sets five-year prison term for kratom cultivation in controlled areas

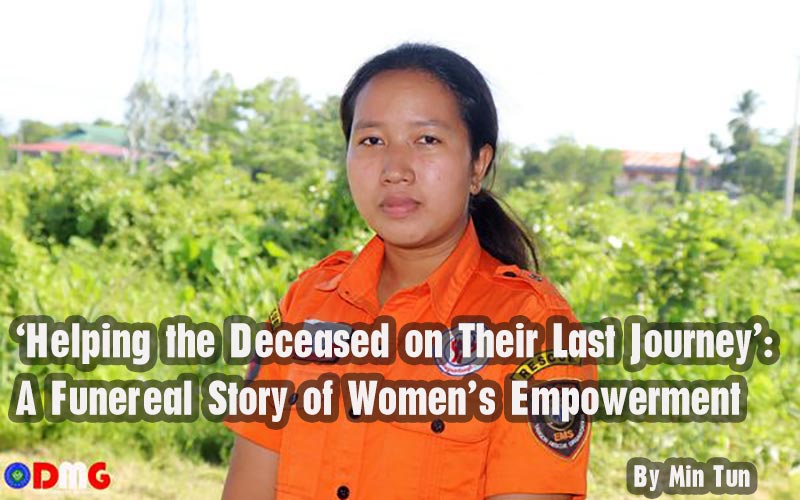

‘Helping the Deceased on Their Last Journey’: A Funereal Story of Women’s Empowerment

Generally, pallbearing has been considered the domain of male volunteers among the various “free funeral service” associations across Myanmar. But a group of young women in Sittwe are playing an integral part in the free funeral and social welfare services offered in the Arakan State capital.

22 Jul 2021

By Min Tun

Women in orange shirts and black trousers carried a coffin from a hearse to the open hall at the ceremony and waited until the monks finished reciting chants as the last rite of the funeral. Then, they brought the coffin to the crematorium.

Generally, pallbearing has been considered the domain of male volunteers among the various “free funeral service” associations across Myanmar. But a group of young women in Sittwe are playing an integral part in the free funeral and social welfare services offered in the Arakan State capital.

Ma Nilar Soe, a 23-year-old from Pan Myaug village in Arakan State’s Minbya Township, is a member of the Shwe Yaung Metta Foundation. She has also taken on the name May Payit since she joined the Sittwe-based social welfare organisation, which is challenging gender expectations when it comes to free funeral services.

“Our social welfare service provides different help, including funeral services. I assist at the funeral service. In our village, people see funeral services as the work of men. People from my village ridiculed me when they saw I was helping to carry dead bodies,” Ma Nilar Soe said.

She was stung by the criticism. Male acquaintances and peers looked down on them as the men thought females could not work for a funeral service, and “some people do not want to talk with us because we are assisting with a free funeral service,” Ma Nilar Soe added.

Ma Nilar Soe has a degree in Myanmar literature, and before she joined the social welfare association she worked as a middle school teacher at a private boarding school in Sittwe for about a year.

She joined Shwee Yaung Metta Foundation in December 2019. She said she joined to help people.

When she started at the foundation, there were only three female volunteers, and 13 male volunteers. She eagerly offered her time and help on a range of foundation activities, challenging notions of any inherently “male” or “female” qualification for anyone doing anything in this line of work.

When she was providing help by soliciting donations or doing other charity work, there was no difficulty for her, but she admits she was apprehensive when she started giving her time to funeral services.

She’d carry the body from the leg end so she did not see the face of the dead, she said.

“When I accidently saw the face of a dead body, I could not sleep that night. The face overwhelmed my eyes the whole day. After I carried the dead body of a drowning case, I couldn't eat my food because I remember the smell of the decomposing body,” she said of the challenges she faced at the beginning.

She struggled with these issues for about a month, but these days Ma Nilar Soe is handling the stresses, and she credits her senior colleagues and bosses with getting her to this point.

“Now, I work my best for the deceased with the belief that they can pass on to another life well,” she said.

The ridicule from some of the people who she worked with as a pallbearer eventually reached her mother.

“My mother told me that I had graduated and she’d helped me to pursue my education till the end, but that it [an education] is not for carrying dead bodies,” she said.

She explained that social welfare activities include all aspects of life, including death.

“My mother understood when I explained, and she accepted my work finally,” Ma Nilar Soe said.

Her parents own farmland and are able to earn a decent living in the village. That allows her to work at the social welfare association without needing to think about her family’s financial wellbeing.

Women who work in the free funeral services have faced many challenges, but they continue to overcome them.

“People see it as inferior work,” Ma Nilar Soe said. “They do not want to talk to us because we are working at ‘an inferior job.’ But we see that our work is helping the deceased on their last journey. When we see a funeral is finished well, we feel delighted about what we have done.”

Funeral services are just part of the work, however.

“We help people who are facing difficulties being admitted to hospital or being discharged from hospital. If they do not have money to return home after medical treatment, the foundation helps them to transport them to their village. So, villagers know that the foundation is working not only for funeral services but also for charity works,” Ma Nilar Soe said.

All of these needs have increased dramatically amid the ongoing third wave of Covid-19 in Arakan State and the rest of Myanmar.

Today, there are 35 men and 25 women members at the foundation. Ma Nilar Soe is now the leader of women aid workers and manager of the foundation’s free funeral service.

“As we help people from villages, they can return home without worries. They say thank you. They say they could not think of what trouble they would face in the town without us because they do not know anyone in Sittwe. I feel happy hearing they are OK because we helped them,” Ma Nilar Soe said.

Ma Nilar Soe says she has decided to work in charity activities until the day she dies because she likes to help others. That decision would have surprised her not long ago, she admits, but words of gratitude bring a priceless happiness for social aid workers like Ma Nilar Soe.

“I am happy to help others. But I did not think I wanted to work in charity activities till the end of my life. When we helped people, they appreciated our help. Because of their words of thanks, I keep doing charity work,” she said.

Ma Nilar Soe as well as other female social aid workers at the foundation were able to overcome the ridicule of some around them because of their dedication and commitment. They’ve proven that women can work abreast of men in any social welfare endeavours, contrary to the assumptions of many of those men.

“To become a person admired by the people,” Ma Nilar Soe says of her goals.

Whenever an ambulance passes a Sittwe road with siren blaring, or a group of women is seen pushing a cart bearing coffin to crematorium, Ma Nilar Soe and the other women and men of the Shwe Yaung Metta Foundation are likely to be playing their part to facilitate the final journey.

.jpg)