- Junta launches major offensive to retake strategic Mawchi mining town

- Extreme poverty drives Sittwe residents to dismantle abandoned houses for income

- Weekly Highlights from Arakan (Feb 23 to March 1, 2026)

- Over 300 political prisoners freed from 10 prisons nationwide

- DMG Editorial: Between War and Opportunity - A New Border Reality for Bangladesh and Arakan

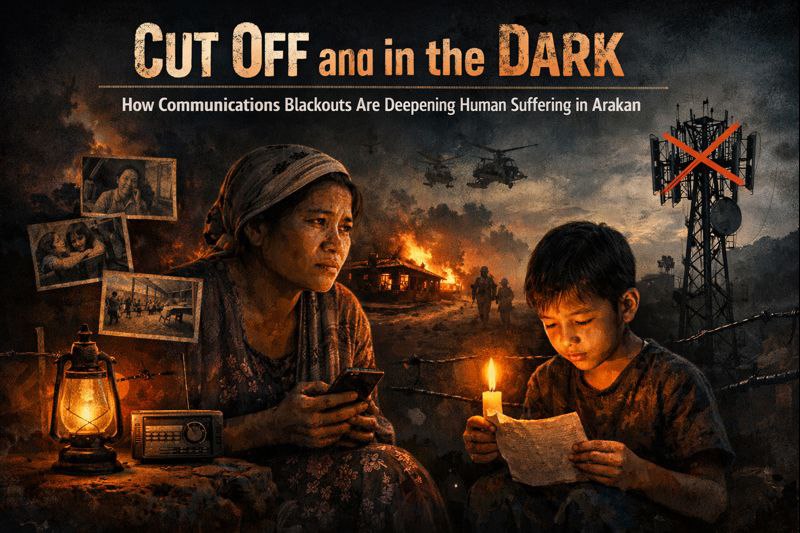

Cut Off and in the Dark: How Communications Blackouts Are Deepening Human Suffering in Arakan

Arakan State, rich in ancient cultural heritage and scenic landscapes, has not only been fighting a ground war since late 2023, it has been plunged into an information blackout that cuts deep into daily life, survival, and human dignity.

18 Jan 2026

By DMG Newsroom | Sittwe, Arakan State

Arakan State, rich in ancient cultural heritage and scenic landscapes, has not only been fighting a ground war since late 2023, it has been plunged into an information blackout that cuts deep into daily life, survival, and human dignity.

Alongside battles over territory, the people of Arakan have faced repeated outages of mobile phone networks and the internet. In many areas, communications have disappeared completely, leaving whole communities in silence unable to connect with relatives, access critical information, or seek help during emergencies.

The Cost of Staying Cut Off

"For organizations like ours, donors pay attention when we can show what we are doing on the ground," says Ko Kyaw Zin Thant, Communications Officer at the Lin Yaung Chi Foundation. "In this situation, internet difficulties directly affect our work. The moment we lose internet access, we lose contact with donors. It impacts us financially."

While the military council has allowed limited phone service in towns under its control such as Sittwe, Kyaukphyu, and Manaung, the rest of Arakan remains under a strategic communications blackout reminiscent of the "Four Cuts" approach. The result: communities are left isolated, and the cascading impact is felt across virtually every aspect of life.

Families Left in Silence

For war-affected families, communication is a lifeline, a way to check on loved ones, seek support, and coordinate assistance. But right now many people go months without hearing a familiar voice, or even knowing whether someone is still alive.

"I want to go somewhere to make a phone call, but I don't have money, so I can't go whenever I want," says Daw Hla Thaw Nu from Ponnagyun Township. "I want to speak with my husband, but the line (internet) isn't nearby. If I go to a place with signal, it's very far. I don't have money to travel there."

In the vast gaps between voice calls, families are left grasping for basic truths: Are they alive? Are they safe?

"I want to make contact to ask how they're living, what they're eating," says Daw Ma Kyaw Sein, a resident of Mrauk-U Township. "But I don't even know if they're alive or dead. If I die, they won't know. If they die, I won't know either."

A Deepened Information Darkness

Arakan's communications shutdown isn't new. Severe restrictions have been in place since 2019, including one of the world's longest internet blackouts. But the current landscape is darker and wider decimating social cohesion, economic exchange, and human resilience.

The military council has intentionally cut communications, analysts say, to conceal battlefield setbacks and restrict information flow. Meanwhile, even as the United League of Arakan/Arakan Army (ULA/AA) has expanded control in parts of the region, security concerns have limited broader restoration of services.

In some AA-controlled areas, residents have attempted to use satellite internet like Starlink only for equipment to be confiscated or access limited for security reasons. Even where satellite services are permitted, costs and connectivity issues keep the technology out of reach for most.

Culture and Minorities at Risk

The blackout affects not just the majority community, but also marginalized groups whose cultural survival depends on connection.

"For society to develop, people must be able to reach one another so we can discuss social, economic, and religious matters," says U Kyan Thein Maung, Chair of the Daingnet (Thet Khamak) Literature and Culture Association. "If this continues, even leaders can't express what they want or make decisions. Losses from all directions could follow."

A Generation Lost to Disconnection

Young people, Arakan's future, are especially hard hit. Without internet, online education and university opportunities vanish.

"As young people, we can't study the subjects we're interested in," says Ma Khin Yadanar Htun, a displaced youth in Rathedaung Township. "The internet is cut, and we can't use it. We don't have opportunities to learn what we're passionate about. Compared to young people elsewhere, we're suffering real disadvantages."

Economic Missteps in the Dark

Local markets are also suffering not just from conflict, but from not being able to track prices or market information.

"Now there's no phone line," explains U Maung Hla Kyaw, a Kyauktaw resident. "If we buy something, we don't know whether prices have gone up or down where we buy it. Then we sell it at a price we think is right but when we go back later to buy, the price has increased. That's what's happening to us."

Information was always the currency of a modern economy, now that currency is gone.

Relaying Truth in the Silence

With internet inaccessible for most, state-controlled radio and television like Myawaddy TV often become the only available sources but they offer propaganda, not truth.

"If there were internet, you could verify one piece of news after another," says Ko Kyaw Zin Thant. "Right now people encounter a story but can't confirm whether it's true or false."

A small number of households can watch independent channels such as DVB or Mizzima, but shortages of electricity, solar systems, and batteries along with soaring prices means most people have lost vast parts of their right to information.

In this environment, local journalists have become a critical lifeline for the region. But they, too, struggle: unable to reach sources easily or transmit their reports, constantly improvising to keep even a trickle of verified information flowing.

"When internet and phone lines were cut, journalists in Arakan could no longer contact the sources they had before," says freelance journalist Aung Soe. "They had to rebuild new networks, for example, by contacting people who were still online through Facebook and other means." The Price of Staying Cut Off The absence of communications does more than block news, it accelerates breakdowns in health, education, livelihoods, and community life.

"In the current period, I see media as absolutely crucial," says Ma Hla Win of the Mro community in Ponnagyun Township. "For news to reach the public, media matters. If the ULA/AA side can help media outlets by enabling internet connections, then these times can become the best possible."

Eyes and Ears Bound

Cutting communications in today's age is like binding a person's eyes and ears.

For the people of Arakan, the day they can hear their family members' voices again, and freely access accurate information, will be a day they reclaim human dignity that conflict and silence have stripped away.

But for now, in the information void, people wait asking a question that grows heavier with each passing day: When will the networks return, so that life can begin to breathe again?